The climate impact of Australian nuclear power

by Alex Harvey

Introduction

Recent Frontier Economics modelling has been used by the Coalition to argue that its proposed nuclear power rollout in Australia would be $263 billion cheaper than the government’s renewables-only plan. The modelling ostensibly shows that nuclear is a cheaper and more practical pathway, but also suggests a short-term delay in decarbonisation — a point some critics have seized on to claim that the two pathways are not comparable, as they fail to maintain equivalent emissions trajectories.

Writing in the AFR and on Twitter/X, economist Steven Hamilton calculated that the nuclear power plan would result in an additional 1,000 million tonnes of CO₂ emissions by 2050:

The modelling shows that this will generate two and a half times the emissions from electricity generation from 2025-2051 than Labor’s plan. That represents 1 billion tonnes of emissions, and that’s ignoring additional emissions outside the electricity sector.

A billion tonnes of CO₂ sounds like a lot. Is he right? And should policy makers be concerned?

In this article, I’ll argue no, and no. Even accepting these numbers at face value, I’ll show that the warming impact of an additional 1,000 MtCO₂ is just 0.000708°C — far too small to even measure. I’ll also contend that the claimed 1,000 MtCO₂ is exaggerated anyway, with 200 MtCO₂ perhaps being a more realistic estimate. Finally, I’ll demonstrate that any slight delays in decarbonisation in the short term are more than offset by greater long-term reductions in the second half of the 21st century and beyond, ultimately making the nuclear plan the more effective pathway to reducing CO₂ levels.

An additional 1,000 MtCO₂

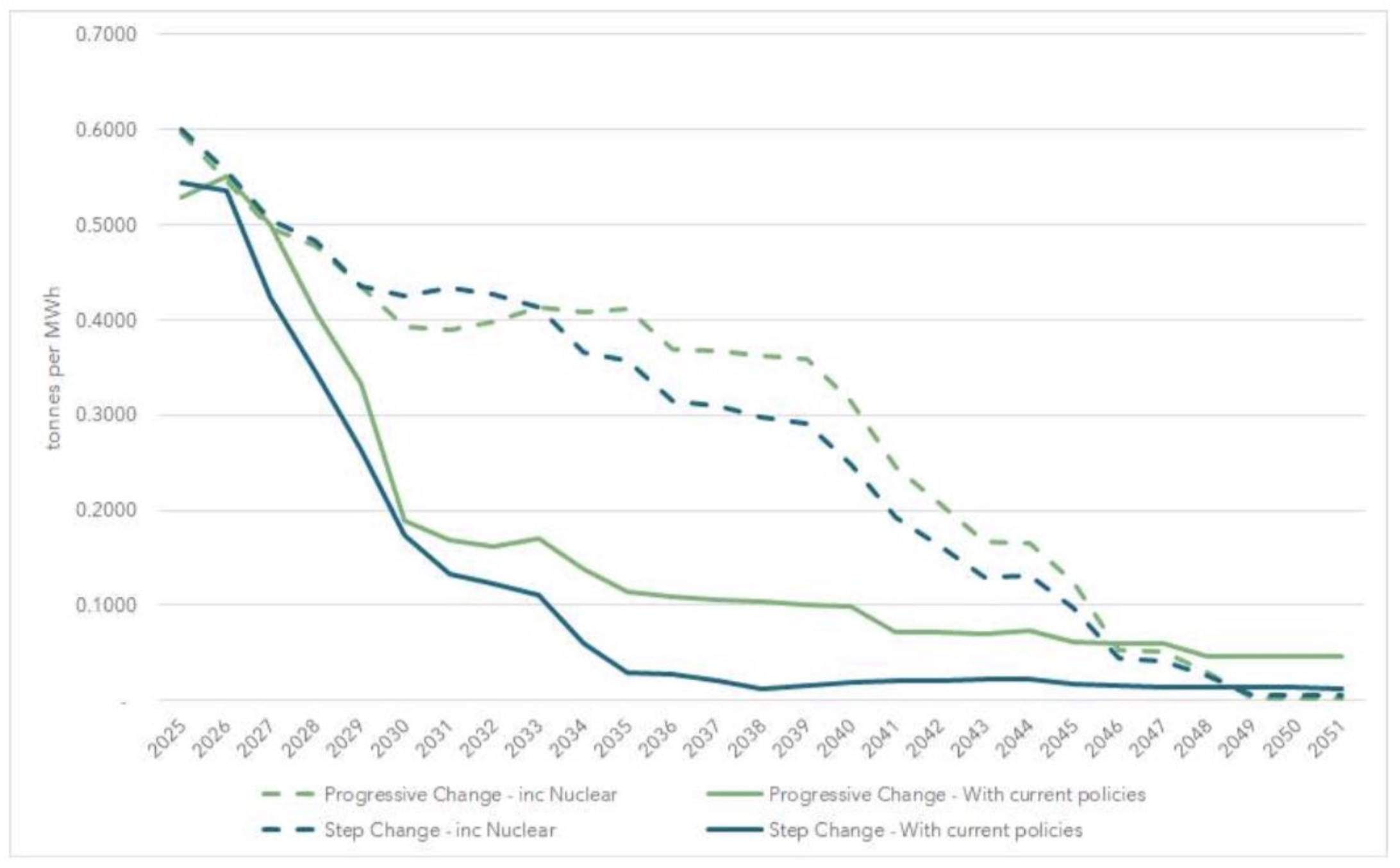

A widely held concern about nuclear power is that nuclear power plants are slow to build. Building nuclear power plants in Australia, therefore, could lead to delays in the phase out of high emissions coal-fired power plants. Considering AEMO’s modelling as is, Frontier compares the existing plan and the nuclear plan by evolving emissions intensities:

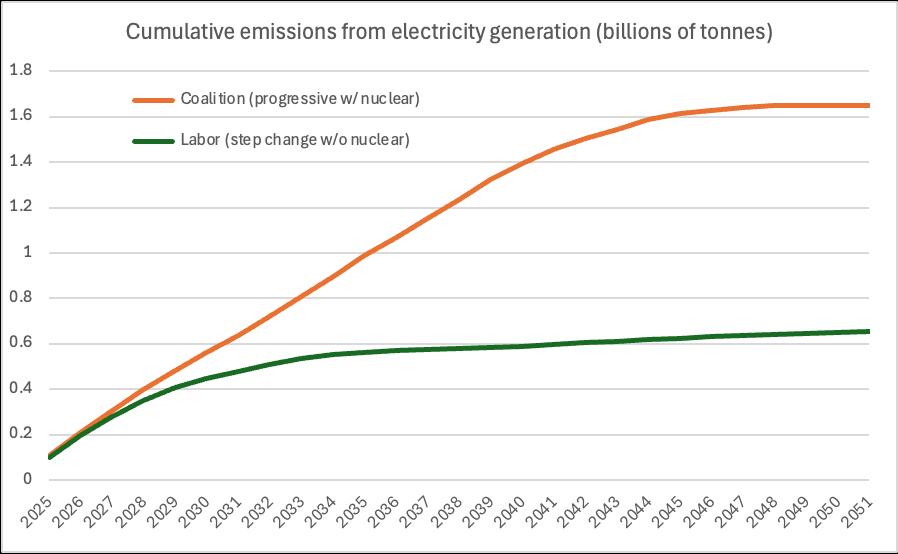

Hamilton calculated that the nuclear plan would result in cumulative emissions of 1,000 MtCO₂ by 2051:

An additional billion tonnes of CO₂ is a seemingly large amount, but its actual impact on global warming is negligible.

In climate physics, the transient climate response (TCR) measures the immediate global warming impact of a doubling of CO₂ above the pre-industrial baseline. The current best estimate, as provided in the IPCCs Sixth Assessment Report, places the TCR at ~ 1.8°C per doubling of CO₂.

The following formula is used to calculate the global warming at the surface (ΔT) for a given increase in CO₂:

\[\Delta T = \text{TCR} \times \frac{\ln\left(\frac{C_{\text{final}}}{C_{\text{initial}}}\right)}{\ln(2)}\]Where:

- \(C_{\text{initial}}\) is the initial CO₂ concentration in the atmosphere (~470ppm in 2045, see below),

- \(C_{\text{final}}\) is the final CO₂ concentration after adding the additional emissions.

Note that 1ppm (“parts per million by volume”) CO₂ is approximately equal to 7,800 MtCO₂, thus 1,000 MtCO₂ increases the atmospheric CO₂ concentration by 1,000 / 7,800 ≈ 0.1282ppm.

To calculate how much actual warming would be caused by Australia emitting an additional 1,000 MtCO₂, we also need to know what the atmospheric concentration of CO₂ in 2045 would be. (Because CO₂ becomes less and less able to raise the surface temperature as CO₂ levels increase, we need to predict what the concentrations in 2045 will be rather than use today’s concentrations.)

Let’s try two scenarios:

- The world is on track for Net Zero in 2045 and Australia is the laggard, in which case atmospheric CO₂ in 2045 might be ~ 440 ppm.

- The world has made little progress and is on track for 3 degrees of warming, in which case atmospheric CO₂ in 2045 would be ~ 470 ppm.

Using the above formula:

\[\Delta T = 1.8 \times \frac{\ln\left(\frac{470.1282}{470}\right)}{\ln(2)} \approx 0.000708^\circ\text{C}\]Thus, the likely case is that an additional 1,000 MtCO₂ would warm the planet by ~ 0.000708°C.

(And the best case is 0.000750°C, in the unlikely scenario that the world actually achieves Net Zero by 2050.)

A more realistic baseline

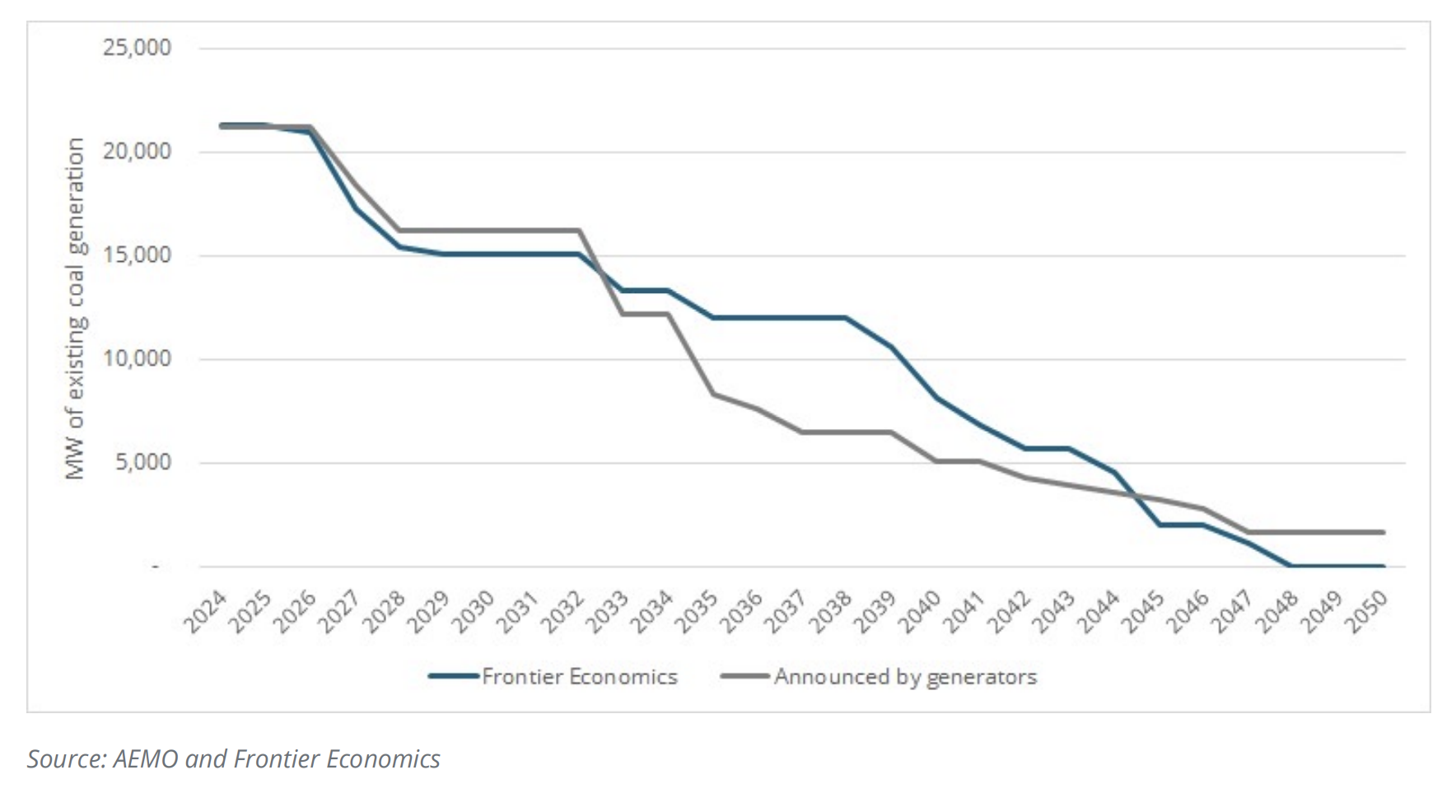

But the figure 1,000 MtCO₂ is almost certainly too high, due to the unrealistic rate at which coal generators are assumed to close in AEMO’s decarbonisation plan. Note that AEMO’s Step Change closure rate is not based on closure dates flagged by the coal genererators themselves or on modelling, but by AEMO simply assuming that the government’s renewable energy and decarbonisation targets (which themselves were not based on credible modelling) are met (ref).

Is there a more scientific estimate? The respected Endgame Economics group (commercial-in-confidence, private communication) have predicted that it would be difficult in practice to even meet the Progressive Change coal closure schedule. Their best estimate of the likely closure rate sees the Step Change budget exceeded by ~ 800 MtCO₂. Note that this aligns well with what Frontier Economics have noted themselves, namely that a closure schedule based on closure dates announced by the generators themselves sees little difference to the nuclear plan (p. 8).

This would leave a difference of 200 MtC0₂ (~ 0.000149°C) between the renewables-only and nuclear plan (and 200 MtC0₂ is coincidentally also the difference between Endgame’s nuclear scenario and their best-case for renewables.)

Second half of century

What matters more, however, is the second half of the 21st century and beyond, and Australia’s transition to a truly zero-carbon energy system.

Many are unaware that the full effects of CO₂ emissions take hundreds to thousands of years to materialise due to the slow response of the climate system, particularly the oceans and ice sheets (ref). While much of the focus is on emissions reductions by 2050, the second half of the century — and beyond — is actually just as critical. Sustained low emissions during all of these periods are essential to stabilising the climate system and avoiding irreversible warming for future generations.

According to the ISP model used by Frontier Economics, the nuclear-inclusive plan produces 0.0054 tonnes CO₂/MWh compared to 0.0072 for Step Change by 2051. These numbers however appear unrealistically low and assume close to 100% renewable energy producing our power in Labor’s plan. Endgame Economics meanwhile find continued use of fossil fuels in 2051 and emissions intensity about 10 times higher.

To compute additional emissions in the second half of the century I use this formula:

\[\text{Total Emissions (MtCO}_2\text{)} = \text{Emissions Intensity (tonnes/MWh)} \times \text{Total Energy (MWh/year)} \times \text{Years}\]Where:

- Years \(= 2100 - 2050 = 50\)

- Energy per year \(= 300 \, \text{TWh} = 300 \times 10^6 = 300{,}000{,}000 \, \text{MWh}\)

Thus assuming a saving of 0.0018 MWh (difference between the nuclear mix and original Step Change) that would add only 27 MtCO₂, which would be small enough to disregard. However, it is not realistic to assume that high levels of renewable energy adoption would ever lead to almost complete decarbonisation. Endgame Economics meanwhile sees something of a best case for renewables around 10 MtCO₂ per year by 2050 and, to ensure a like-for-like comparison, they see their nuclear scenario around half that at 5 MtCO₂ per year.

So that would be another 250 MtCO₂ showing that before 2100 the nuclear energy system — despite delaying coal closures relative to the ISP assumptions — ends up more impactful in the fight against climate change.

Conclusion

This analysis demonstrates that concerns about an additional billion tonnes of CO₂ resulting from the Coalition’s nuclear power rollout are unfounded. The warming impact of 1,000 MtCO₂ — approximately 0.000708°C — is negligible and too small to even measure. Furthermore, the estimate itself is inflated due to unrealistic assumptions about coal plant closures in AEMO’s Step Change scenario. A more realistic assessment suggests the figure is closer to perhaps 200 MtCO₂ (0.000149°C) by 2050. Importantly, these concerns overlook the long-term benefits of a nuclear-inclusive energy system, which would achieve significantly lower emissions in the second half of the 21st century and beyond.

When accounting for both the immediate and extended climate impacts, the temporary delay in coal plant closures during the construction of nuclear facilities is unlikely to outweigh the substantial climate benefits of achieving a truly low-carbon energy system. Policymakers should therefore consider nuclear power as a viable and impactful option in Australia’s decarbonisation strategy, rather than being deterred by short-term emission projections.

References

- https://www.afr.com/policy/energy-and-climate/economics-of-coalition-s-nuclear-modelling-are-worth-nothing-20241214-p5kydg

- https://www.frontier-economics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Report-2-Nuclear-power-analysis-Final-STC.pdf

- https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/research/climate/understanding-climate/climate-sensitivity-explained